How present are you to your own experience? It's a reasonable question to ask. If the way you see the world is based on the labels mind assigns, does that mean that labels come between you and experience, and you are not really present at all?

Tarthang Tulku - Gesture of Great Love

‘Fully present’ illuminates what we mean by ‘Embodied Ecology’ and how that relates to ‘Connecting to Place’. My March 4th blog entitled: Embodied Knowing is Evolution, well explained that Embodied Knowing is a contemplative practice; not just sitting-on-a- cushion ‘practice’ but also practice within the daily actions of living. I concluded that blog by restating that the central aim of Dharma College Embodied Ecology - both the zoom class and the blog:

is to engage the [climate] crisis by countering the negative interaction between environmental degradation and affective states which diminish environmental agency; nurturing positive affect and creative action. This will be accomplished through contemplative practice of embodied knowing, enhanced human connectivity with the environment – our place.

In today’s blog I will expand on the idea of being connected to the complex phenomenon of our planetary ecosystem through being more ‘present’ to our experience of place, hoping to nurture creative environmental action.

There seems to be two distinct modes of knowing and being. Our ‘rational mind’ deals with finding solutions for problems. ‘Embodied Knowing’ allows direct experience to facilitate ‘intuitive mind’. From the neurocognitive perspective the division of the brain’s functions between the right and left hemispheres are reflected in these distinct modes [Intuition, insight, and the right hemisphere: Emergence of higher sociocognitive functions; Simon M McCrea]. ‘Rationality’ describes the dualistic regime of mind, which may be predominantly a function of the left hemisphere.

The development of critical thinking is necessary for understanding the science of Ecology, so objectivity is truly important. Objectivity necessarily implies an observing subject; subject-object duality is inherent in rationality. The problem with solely relying on objectivity with regard to such a complex system as the Earth’s Ecosystem is that unbridled rationality conducts thinking into a mental singularity and overwhelm. Why? Because rational objective thinking is linear thinking; cause then effect. Rational understanding of the complexity of Earth would need a huge if not infinite computation of interacting cause and effect relationships, so understanding cannot be computable. Perhaps Climate Denialism begins as an overwhelming and incommensurable attempt to rationally comprehend the problems of Climate Catastrophe and Biodiversity Loss.

Our best hope of understanding Climate Catastrophe must transcend linear causality. Again, ecological complexity refers to the intricate web of interactions within an ecosystem, where numerous species, environmental factors, and dynamic processes interrelate in a way that creates emergent properties, meaning the whole system behaves in ways not predictable from individual components alone; essentially, it's the characteristic of an ecosystem where the complex interplay between different elements leads to unpredictable and often self-organizing patterns, making it difficult to fully understand by simply studying individual parts. Nondual knowing offers the possibility of evading the conundrums of complexity and incommensurability by being present to situations without framing a ‘problem’ which demands a ‘solution’ of an unsolvable non-linear dynamic. Tarthang Tulku suggests in Lotus Body:

If it is not a problem, the point of arising might be able to offer so much more: a great many more approaches, resources, and choices. Situations, like bodies themselves, are stages of transition. So what is developing? What parameters of space, time and knowledge could be opened up if we really let go of problems?

It is not a matter of rejecting ‘duality’ and rationality in favor of ‘nonduality’. It’s more like relaxing one’s mind when complexity overwhelms us. We can then embrace our experience - for example - of Climate Catastrophe and Biodiversity Loss. Graphically it might look like this:

Our rational minds are contained within the greater whole of our awareness of being. Inspirationally, Tarthang Tulku writes in Gesture of Great Love:

Interlude

Can you let go of trying to know?

Relax.

Be silent.

Breathe.

Now, walk outside and smile at the sky.

In this month’s (March 2025) Scientific American, in an article entitled: Anatomy of an Insight, Scientists close in on the elusive essence of “aha! Moments,” Philip Ball writes about “flash inspiration... a creative intuitional burst,” and “the Insightful vs. Analytical Brain.” The upshot is that minds well prepared by thinking hard about a problem may transcend reason with a flash of inspired intuition:

The aha! moment brings new ideas and perspectives, lifts mood, increases tolerance for risk, and enhances the ability to discern truth from fiction.

The question: “How present are you to your own experience?” can be a key to harnessing the elusive aha! Presence is not something to be attained or strived for, but rather the natural, inherent state of being that we continuously experience as our embodiment. Embodied Knowing requires being fully present to your own experience. Embodied Knowing becomes Embodied Ecology through connectivity to place, as a manifestation of being structurally coupled to our environment. Recall the 4 E's of Enactivism: embodied, embedded, enactive, and extended, from my February 24th blog – Embodied Knowing. Connectivity to place is a naturally non-dual expression of “Thinking through the Body,” as Pamela Richardson writes:

Our bodies are at the core of our experience of the geographies we inhabit. We live our lives as embodied creatures; feeling, sensing, and thinking through the body. Our relationship to space, place and landscape is inescapably shaped by the kind of bodies we have. And yet our embodiment is often written out of geographical discourse, reflective of a key problem in Western thought: the ontological discontinuities perceived between the social and the natural, body and mind, the self and the world.

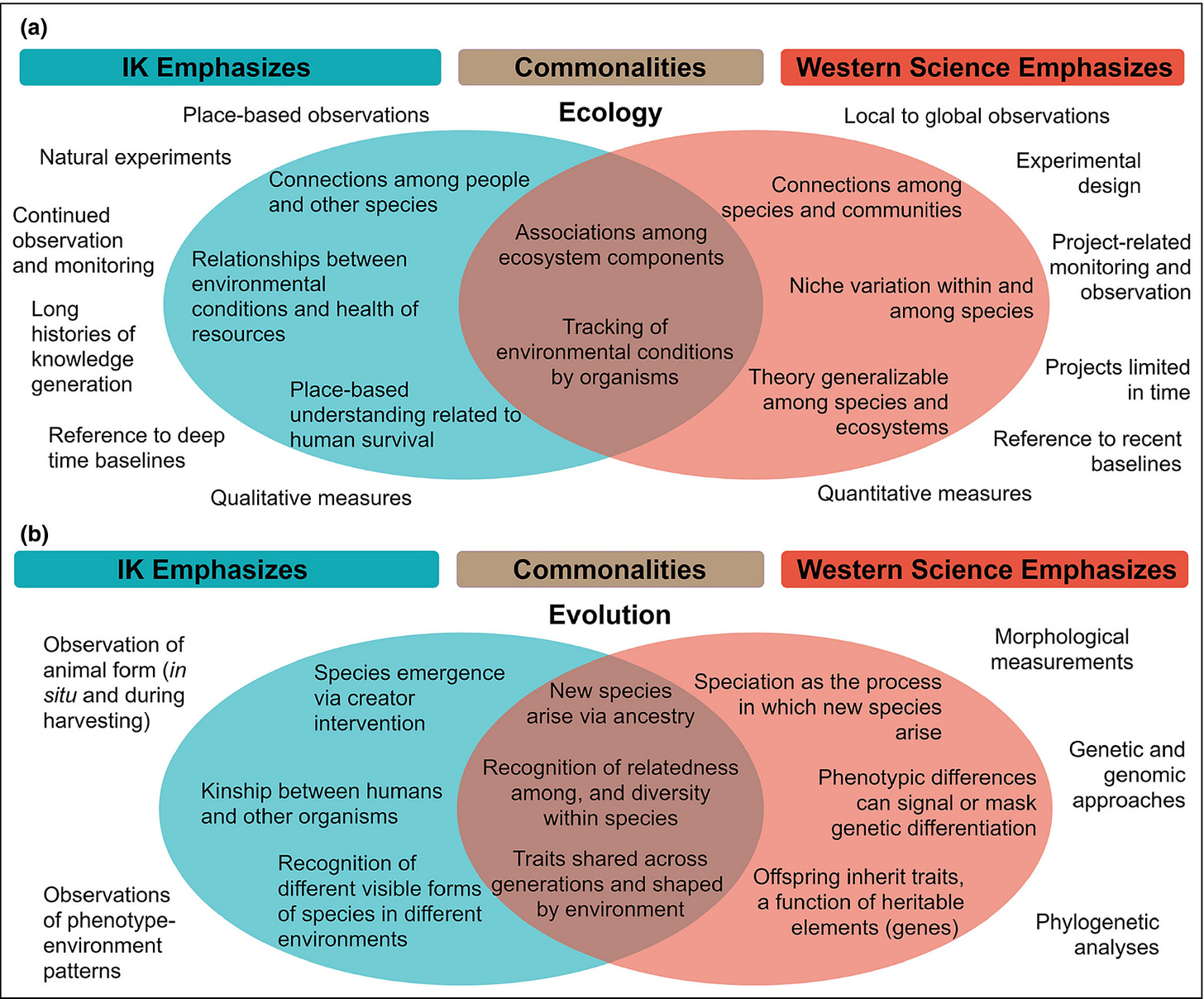

Being present to our own experience allows us to feel at home where we are. It elevates ‘where we are’ to a place we share and care about. We modern Westerners tend to be more loyal to abstractions like money or ethnicity or social class or profession or place of origin. Few of us – at least here in California - are living anywhere near the places our ancestors came from. We feel that we are the opposite of Indigenous, because we are descendants of colonizers and refugees. But what if becoming Indigenous to our place is necessary to protect ecosystems? Indigenous Knowledge (IK), I argue, is Embodied Knowing and is crucial to the central intention of this class/blog:

Engaging the crisis by countering the negative interaction between environmental degradation and affective states which diminish environmental agency; nurturing positive affect and creative action.

Contributions of Indigenous Knowledge to ecological and evolutionary understanding - Tyler D Jessen, Natalie C Ban, Nicholas XEMŦOLTW Claxton, Chris T Darimont

‘Coming home’ embodies knowing who and where we are. Gary Snyder writes in The Practice of the Wild:

The heart of a place is the home, and the heart of the home is the firepit, the hearth. All tentative explorations go outward from there and it is back to the fireside that elders return. You grow up speaking a home language, a local vernacular. Your own household may have some specifics of phrase, of pronunciation, that are different from the domus, the jia or ie or kum, down the lane. You hear histories of the people who are your neighbors and tales involving rocks, streams, mountains, and trees that are all within your sight.

Home, for most modern Americans - not yet practicing embodied knowing - is not a wild place but rather an investment. It is property in a neighborhood that we have colonized. For most of us there are few if any Indigenous people living in our neighborhood. The idea of ‘home’ for Indigenous people is shared with tribe, and aside from actual buildings is a shared Commons. Being, perhaps, wannabe Indians, can we find a middle ground between tribalist and colonist? Can being a ‘commoner’ bestow both access to and agency in land-management? What would it take for community-thinking to promote ecological development and social equity? Historically, the United States opened a great deal of common land, but in the late 19th century the trend in this use swung to business interests.

The practice of leasing and utilizing common lands for business in the US, particularly for resource extraction like minerals and oil, has roots in the 19th century with acts like the General Mining Law of 1872 and the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920, which allowed for private ownership and resource extraction on public lands. Google AI

Can our modern economic systems again allow an open Commons? In feudal England, the commoners were given access to resources by the leave of the lord of the manor. Land use is the crux of ecology. Again, from Gary Snyder in The Practice of the Wild:

The Commons is the contract a people make with their local natural system.

When the Commons are closed and the villagers must buy energy, lumber, and medicine at the company store, they are pauperized.

Realizing the Commons may be the way we discover the embodied-knowing path of becoming indigenous to place, loyal to its ecosystem, and fair to all the people and other beings who live in the place. Realizing the Commons may be a way to show respect for, and become allies with, our few remaining Indigenous neighbors, who we need to show us much of the way and become allies with all the beings we share our home place with. Robin Wall Kimmerer, herself an Indigenous Citizen Potawatomi - and an eco-hero and eco-ally - writes in Braiding Sweetgrass (another high recommendation):

For all of us, becoming indigenous to a place means living as if your children’s future mattered, to take care of the land as if our lives, both material and spiritual, depended on it.

So, I’ve provided lots of conceptual, rational explanation of Embodied Ecology, but of course our purpose is to ‘practice’ a different way of knowing. Reading and conversation are good table setters, but practicing full presence is the meal. Come join us at Dharma College for our next, which will be in the Spring; we’ll have specific dates soon. In the meantime, please subscribe to this blog.